I spent five years in Tanzania ( then called Tanganyika) from 1951 to1956. It was my first job - as a colonial administrator, first a District Officer and later a District Commissioner. I was then fluent in Swahili but it now needed brushing up. To help me, for a month I read a chapter of Luke each day, with the New Testament open in Swahili (Agana Jipya) as well as an English version. I also ordered Teach Yourself Swahili, which came with two CDs and a little book. The result was that when I arrived, I was able to make simple conversations with ease. When Bernard and I were doing fieldwork in Kenya in the 1970s, we visited Tanzania twice; I made two visits in the 1980s on a consultancy with Per Nilsson; I was last in Tanzania in 2007, when I joined Agnes Klingshirn ( who had accompanied me on my September 2010 trip to Ghana) - Agnes was then working on a Siemens/Bosch project, testing cooking stoves run on Jatropha oil. On that visit, I spent two weeks in and near Arusha.

Through my New Zealand friend Mike Sansom I had heard of Daudi (“David” in Swahili) Peterson and his brothers, Mike and Thad, ( whose American missionary parents had come to Tanganyika in the late 1940s) who operate Dorobo Safaris, from Arusha. After reading a fascinating report of a long trip that Daudi made with his wife Trude, I decided to arrange for a safari under their auspices. Denise Ackerman, a 75 year-old retired professor of theology who also lives in Cape Town, had also inquired about a safari, and because we had similar interests, Daudi put us in touch with each other. Denise and I met, deciding that we were sufficiently compatible to go on a ten day Safari, and – after some fine-tuning – an itinerary was agreed on. Many of the fine photographs that accompany this diary were taken by Denise.

Fairview Hotel garden

September 19. Up at 3:30 a.m. for a 4:15 a.m. collection by Trevor, the airport shuttle driver, arriving at Cape Town airport in good time for my 6 a.m. flight to Johannesburg. I was dismayed to learn at Johannesburg that my flight to Nairobi was “ delayed indefinitely”, but in fact we were only a few hours late. On the flight, when I asked (in Swahili) the steward for my sundowner drink, my neighbour asked me where I had learnt Swahili, and engaged me in conversation, which lasted for the whole trip. (Throughout the trip, I was asked this question numerous times, and when I told people that I had been had been a colonial administrator, I was always welcomed warmly: I never met any animus - perhaps distance lent some enchantment?) George Kennedy Motemba, a senior chartered accountant in Kenya's Ministry of Finance, had been at a conference in Johannesburg; we swapped brief life histories, each ordered another drink and got on very well. When I arrived at Nairobi at 9:30 p.m., I was met by Stephen Kihiku, a taxi driver who had been sent to meet me by the Fairview Hotel. When Bernard and I stayed several times at this hotel in the 1970s it was small, charming and with a lovely garden. The only change now is that the hotel is huge, but it retains its charming character.

Nthia & Mary Njeru

Nthia & Mary Njeru

September 20, Sunday. I stayed an extra day in Nairobi in order to see Nthia Njeru, whom we had first met when Bernard and I were doing fieldwork among the Mbeere, in Eastern Kenya, in the early 1970s. We had gone to Kangaru School, in Embu, where the headmaster allowed us to interview the Mbeere boys in the third and fourth forms: we wished to engage a few of the boys as research assistants. Nthia stood out from the beginning, with his bright eyes, eager expression and good English; he helped us both in the school vacations and later during his vacations from the University of Nairobi. He became our best informant and also a good friend . Nthia was awarded a post-graduate scholarship to the United States, and I was able to invite him to do his PhD with me, at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Nthia stayed a few days with us in London in 1985: we took him to the Tower of London, where he remarked, dryly, after reading the turbulent history, and seeing the executioner’s axes, I always thought that we (Africans) were supposed to be the violent ones. He is now Dean of Social Sciences at the University of Nairobi.

Nthia and his wife Mary,Nthia and Mary Njeru at Fairview Hotel .1509 whom we had met first in the 1970s when she was his girlfriend, came to the Fairview Hotel for a long and leisurely lunch by the hotel pool. Mary had been a headmistress when I last saw her, c 1988, but she prefers teaching to administration. She teaches (maths, in Standards 7 & 8) at the primary school of Kenyatta University, a ten minute drive from their suburban home. Nthia drives 20 kms to his office, which can take him three hours: like Accra, Nairobi has daunting traffic problems, and formidable traffic jams.

We had three hours of animated discussion with Nthia and Mary bringing me news of what was happening both in Mbeere, and also in national politics; their 15 (undeveloped) acres in Mbeere, which now has tarred roads and good water supplies; their five children, three of whom are university graduates and two are completing their degrees . In January 2010 Nthia had been held up by robbers, who fired a bullet through the windscreen of his 4 x 4, fortunately not wounding him. Nthia and Mary both urged me to come again so that they could take me to Mbeere to see the changes: this I would like to do. After they left, I had my afternoon nap, followed by 20 minutes swimming in the pool and then a walk around the long block, busy with late Sunday afternoon traffic -- Bishops Road, Ralph Bunche Road, Second Ngong Road, all familiar from my previous visits.

Iraqw Homestead (see below)

September 21. Taxi driver Stephen met me at 5:45 AM to take me to the airport, where I queued for 1 1/2 hours, then boarded a Precision Air flight , (45 minutes) to Kilimanjaro Airport, which serves Arusha, Serengeti and other tourist destinations. There I was met by a smiling driver, David, who had been sent by Daudi to collect me. David had spent three years of college in Arusha, doing wildlife courses in preparation for being a guide. It took him 1 & 1/2 hours in heavy traffic to take me the 50 kms to Daudi's home, which is on the other side of Arusha. There I stayed in their comfortable guest cottage, set in an exuberant tropical garden (Daudi had kindly invited me to spend a couple of days in the guest cottage, both before and after our safari). When I arrived, Trude, (Gertrude) Daudi's wife, was playing games in the garden with 10 little children, both black and white: she runs a kindergarten. At lunch I met Daudi and also Mika, their 22-year-old son who had graduated from Olympia College in Evergreen, Washington and had enrolled for a six months wildlife course at a college in Limpopo Province, South Africa.

After lunch I was collected by Peter Russell, who had been a student of ours in Environmental Studies, at UCSB in 1986. Peter and his wife Tammy met in a course Environmental Problems of the Third World, which Bernard and I taught jointly; we were at their wedding in 1987. They are missionaries,(“Wild Hope”) having spent nearly 10 years in Kenya until illness forced Peter to return to the US. From 2004 they have lived in Arusha, doing leadership training, arranging business loans, and sports fellowships. Tammy has home-schooled their four children, the eldest two now being at college. The whole family speaks not only Swahili but also Maa, the language of the Maasai, which is understood by the local Wa-Arush people. On my last visit to Arusha in 2007, Peter and the elder boys had taken me for a memorable day on Mount Meru.

the Russell family

the Russell family

After tea with Tammy and their 13-year-old twins, Leighton and Sianna, Peter drove 15 km to show me their 26 acre plot of land, which they had on a 66 year lease. It is a wonderful location with views of Mount Meru, Kilimanjaro, and the Maasai Steppe. They hope to build a house there, eventually. Returning at dusk, I enjoyed the happy family atmosphere, and a good supper.The Russell family 1519a Peter told me more about his work - providing microcredit to the Maasai seemed initially to be a good idea but most recipients spent the money to buy more goats , which are environmentally destructive.

Mount Meru

Peter was also encouraging selected young men and women to specialize in studying ornithology, as they could find jobs as guides to birders/tourists. Tammy had found a good designer to help the Maasai women make high quality jewellery which could be sold in the US. I saw some marvellous examples of angels and butterflies made by these women.

Wild Hope jewellery.

I heard much about the controversial gift of hunting land to the Saudi royal family, which would entail the removal of nine Maasai communities, who were bullied by the police, many having been forcibly removed ; rapes and deaths were reported. However, the Maasai are protesting and have engaged lawyers to sue the government. At the moment there is a lull before the elections, due to be held at the end of October; after the election there may be a compromise, allowing the pastoralists to control the land but also permitting limited hunting. (When I asked why the Arabs had so much influence, I was told that each year a 747 jet is sent from Saudi Arabia to take the president of Tanzania and his entourage to Dubai, where they are all given credit cards and can buy whatever they like , providing their purchases would fit on the aircraft. I was not able to confirm this story). Peter and Tammy reminisced about their days at UCSB , and about Bernard, who had supervised both of their Senior theses, and who had clearly been a strong and positive influence on them. They remembered coming to our home for Sunday lunch parties, saying yours was the only ‘professor’s home’ we visited, in our four years at university. Perhaps it was in part because we did not have our own children, but Bernard and I enjoyed hosting our regular student parties. After supper, Peter thought nothing of driving me back right across Arusha, about 15 kms. where I had a good night’s sleep in the guest cottage.

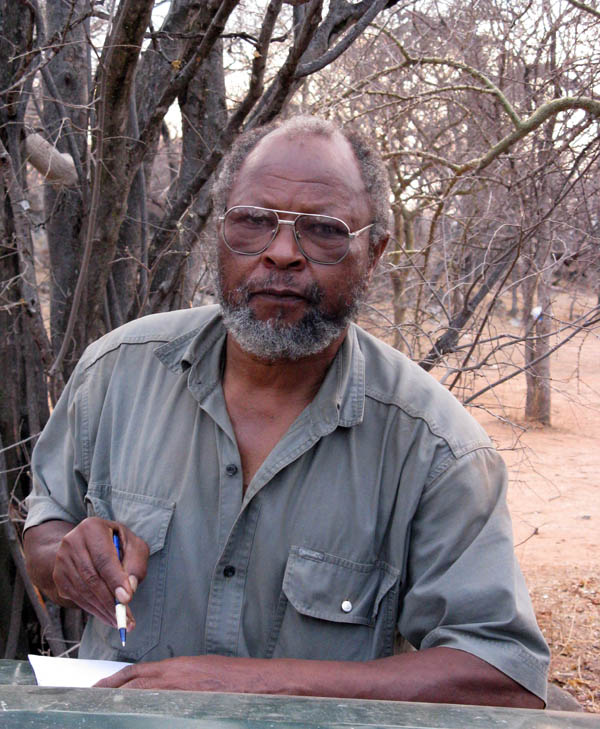

Pallangyo

Pallangyo

September 22. The first part of the morning I spent in reading Daudi’s folder of materials about the Hadza, who are a small group of hunter gatherers. The leading authority on the Hadza. is James Woodburn, a social anthropologist now retired from the London School of Economics. Woodburn, who made his first study of the Hadza in 1958, has written a series of scholarly articles as well as impassioned pleas on their behalf. In a statement the Hadza said, in effect : We are not opposed to development; we also need education -we need a pool of educated members; we would like clean accessible water which is community owned and controlled; a medical mobile clinic would be good. But we want the sort of development that allows us to keep our cultural heritage. I summarise in an appendix some of what I learnt about the Hadza and about their relations with Dorobo Safaris. They live in the Yaida Valley, a few hours drive to the west of Arusha , where no more than 200 still follow the hunter-gatherer way of life. Both Denise and I were interested in the Hadza and we hoped to see something of them. We admitted to each other that we had misgivings about visiting the Hadza, hoping that we would not simply be voyeurs, as is the case of much “ethno-toursim”. Later we realized that we need not have worried : Daudi had established exemplary relations with the Hadza, and I could fully agree with him when he told me: there is no doubt that they are better off with our cooperation, in terms both of cultural survival and of human dignity.

Later in the morning Daudi gave me a guided tour of part of their 60 acre estate; where they have a staff of about 60, including guides, drivers, cooks, gardeners, clerks, IT specialists and administrators. I saw their impressive fleet of vehicles ,with about 20 Land Rovers, all in good order, neatly lined up, and under cover – in contrast to the usual chaotic state of East African government vehicles, many of which have broken down and been left to rust away. I saw a 1949 short wheelbase Land Rover which was being restored; this reminded me of my first vehicle, a similar sturdy model which I bought in Handeni , Tanganyika, in 1952 and which gave me outstanding service under often very rough conditions. We had time for some birding before lunch, Daudi being an expert birder. We saw 13 species, including three that were new to me -- an Ayre’s hawk eagle, a black crake, and a Taveta Golden Weaver. I was surprised to meet two zebra ambling on a footpath ; Daudi told me that four years ago they were being chased by young men with machetes when they were rescued by Daudi’s staff. They had probably escaped from a live animal park, and were now semi-domesticated. Daudi introduced me to Senyaeli Pallangyo (“P” henceforth), who was to be our guide, an impressive man, about 65 years old, about whom I will have more to say later.

That evening Daudi and Trude had guests, Ian (A.R.E.) and Anne Sinclair. Ian is a well-known ecologist, with years of experience in East Africa, and conversation was lively – and the vegetarian supper was superb. I heard more about the proposed road through Serengeti National Park , which has been criticized by the World Bank and by many major Western environmental organizations because of the disastrous impact it would have on Serengeti. Even the Arabs are against it, because it would interfere with hunting. Ian Sinclair thought that the road would be paved with murram initially, and that later it would be tarred , because of heavy truck traffic. After human and animal lives had been lost , the road would be fenced and that would be the end of Serengeti. Again nothing is happening until after the elections, and there is some hope that shortage of funds will delay the construction of this road and that eventually they might choose a southern route which would have a minimal environmental and social impact. (Ominously, China seems to be waiting in the wings; possibly they will fund this ill-considered project). Each year in October / November Dorobo Safaris hosts a group of students from Lewis and Clark University, who come on a six-week visit to learn about the ecology and biodiversity. Daudi welcomed the opportunity to influence future leaders.

Camping in Noa Forest

Camping in Noa Forest

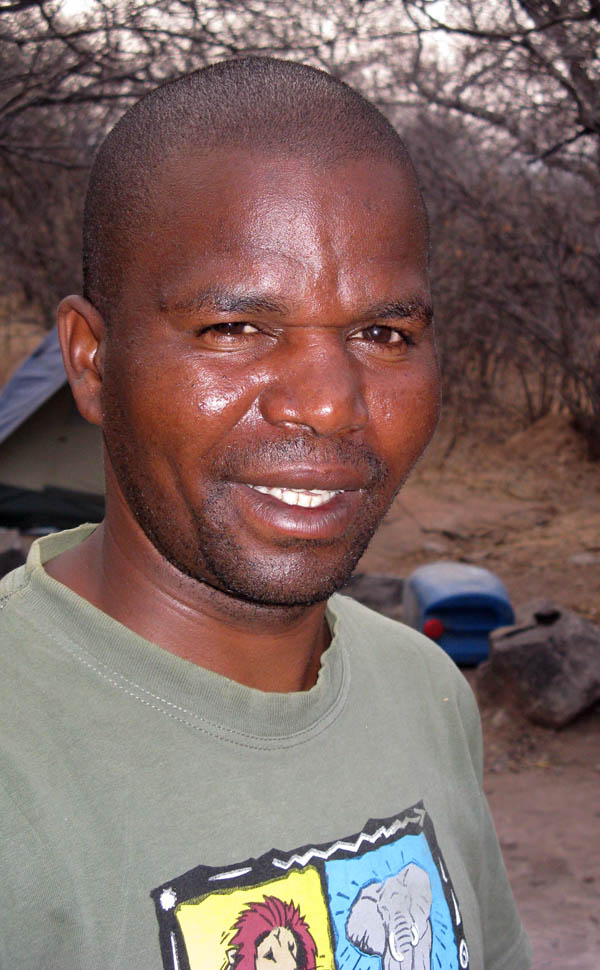

September 23. Denise had been expected to arrive the previous evening but her flight had been delayed and she only reached us at 11 a.m. Shortly afterwards, we set off, on the main road westwards, to Dodoma, in a Land Rover driven by P with his assistant Kisana Mollel ,who was to be our cook, assistant driver and general help . P is a Mmeru, and Kisana a Mw’Arush, and they had a relaxed and easy relationship, although K was always respectful to the older man. Julius Nyerere deserves credit for down-playing “tribalism”, and for forging a Tanzanian identity, helped by the vigorous promotion of Swahili as a national language. P is a retired game warden; when he was with the game department he accompanied a sort of “Noah’s Ark” on a ship to Cuba, when the president of Tanzania had presented Fidel Castro with a selection of game animals. After an hour on the road westwards, Kisana remembered, with profuse apologies, that they had packed only one tent, so they phoned the office, which arranged for a vehicle to bring us the extra tent . While we waited, Kisana prepared a simple picnic lunch and we did some bird-watching -- Denise is an avid and knowledgeable birder, as are both P and Kisana, so nobody complained when we spotted a new bird and we stopped, lifting up our binoculars to identify the bird.

Pallangyo and Koroni

Pallangyo and Koroni

We had a bumpy drive crossing the Rift Valley and then up a steep , curving rugged road to the Noa forest , which we reached at dusk, just in time to put up our tents. I had not camped for many years but this was very easy camping, Denise and I each having a two-person tent with a comfortable bed; there were separate small tents for a loo and a shower. Waiting for us where two Iraqw men, Andrea and Korili, who were our helpers and guides for the next two days. Dorobo Safaris has an arrangement with these local people, as they do with the Hadza, so that each group receives an annual subsidy plus a set amount of money for each guest night, as well as advice and support. The money is given not to individuals, but to the local council, which decides on how it will be used.

Sundowners

Sundowners

September 24. At an elevation of over 5000 feet it had been a chilly night, but we were warm in our tents.

After a hearty breakfast, prepared by Kisana, we set off with P and Koroni, one of the Iraqw guides, on a long 4 & ½ hour walk through wonderful primeval forests. We saw few animals and few birds, but we did see droppings of hyena, dik-dik and elephant, and we frequently heard that tantalizing call of the Turaco, which abound in these forests -- but we did not see one of these colourful birds.

P told us more about the arrangement that Dorobo Safaris has with the local village council: men are allowed to graze their cattle at certain times, but there is no poaching and no cutting of trees. Other villages ignore these restrictions. We also heard more about the Iraqw, who are a Cushitic group, with very “Ethiopian” features. The local “village”, Madonga, has a population of about 400, in 600 homesteads; they grow corn, beans and millet, and every ward must (by government edict) have a secondary school. The last part of our walk was uphill which left me short of breath. When I had last seen Geoff Duncan, my excellent GP, he said that excess weight round my waist was causing the shortness of breath: I will have to remedy this. On return to the camp I had a refreshing shower -- a 15 L bag had been put in the sun and I had warm water.

Our late afternoon walk took us to a vlei, where we met the cheerful young chairman of the ward, riding his piki-piki (motor-cycle), and we had a good discussion. Returning to camp, we had good views of two Sykes monkeys scampering about high in the trees above us. I enjoyed my Serengeti beer, sitting around the fire, before Kisana’s tasty dinner.

Three Hadza men

Three Hadza men

September 25. We packed up camp, and set off for the Yaida Valley, to meet the Hadza. We stopped at a roadside village so that P could buy 1 kg of 5 inch nails which the Hadza had requested, to make their arrows. P also bought 15 x 250 g bags of salt for the Hadza. It was a longish drive and we reached our campsite, not far from a Hadza settlement, in the late afternoon. Denise and I were introduced to a group of Hadza men and women who were waiting for us. Amina and Severia seemed to be the most experienced of the women; among the men we met Maloba, who proudly showed us the high quality American knife which Daudi's son Mika had given him. Later he demonstrated his skills with his bow and arrow. Ng’anjo was a younger man, They taught us a few words of their language, including the greeting Mutana. All spoke Swahili, as well as their own click language.

Women digging

Women digging

Denise, P and I had a good chat around the fire after dinner. P has a questing, lively mind, and in the evenings he liked to quiz Denise and me, asking us subtle and difficult questions, such as What is intuition? What do you think of Ahmed Deedat, he is from your country? (I had never head of this South African Indian, 1918-2005, a radical Muslim missionary, notorius - as I saw when I Googled him, later - for his anti-Christian debates and polemics). P said that he was going to take advantage of travelling with “my two professors”. Although P and I often spoke in Swahili, he was really humouring me, as his English was far better than my Swahili, and he had an excellent knowledge of idiomatic English. He was extremely critical of African leaders, especially Robert Mugabe and Gaddafi, thought little of Jakaya Kikwete, his own President, but greatly admired Nelson Mandela: that man is my hero. By 9 p.m. we had gone to our beds.

Honey

Honey

September 26. After breakfast we set out for another walk, which again involved some steep climbs. Ng’anjo noticed my discomfort and quickly and expertly cut a walking stick. Ng’anjo used the back of his axe to hammer pegs into a baobab tree so that he could climb up and get the honey from the stainless bees. Honey in tree Honey.DA2483

(2 separate pics) Hangate showed us how he made fire. We followed a lesser honey guide (P told me the name, Indicator minor) but we lost it in the hills. On the way back Hangate shot a dik-dik with his arrow. Denise and I were sad at the death of this pretty little antelope, but we appreciated how welcome the extra protein was to our hosts. While we were resting, P said your country South Africa makes good tools; holding up a machete he said: We get most of our best tools – hoes, machetes spades and axes - from your country (South Africa) and Brazil, very few from China.

P was intrigued by my colonial background, and liked to introduce me, proudly, Huyu Mzee anajua kiswahili , na yeye alikuwa DC, zamani sana “this old man speaks Swahili, and he was a District Commissioner, long ago”; then I would be tested in my knowledge of the language. He reminded me of a proud Jewish mother showing off her son’s accomplishments. ., who was just old enough to remember the last of the colonial days, told me that he wished he could have seen me as a Bwana Shauri - “Mr. Affairs”, the term for a District Officer. He used to call me, jokingly but affectionately, Bwana Shauri, which I loved.

Our new friends, the Hadza, had agreed to take us for a late afternoon walk; after waiting a little while , when they did not turn up, P took us on his own for a quiet stroll. Later, they told us casually that they had gone to collect firewood. Denise and I were pleased at this demonstration that they were manipulating us, rather than the other way around : we were clearly there as their guests, on their terms.

Kisana had prepared another good meal from the huge array of supplies that he had brought, far more than Denise and I could eat, but nothing was ever wasted. I was dismayed to note that both the mayonnaise and the tomato ketchup came from the United States; however the honey and the ukwaju, (tamarind juice) were both locally made, and delicious. When we asked Kisana to prepare a simple lunch, he gave us a good selection of mango, orange, pineapple and watermelon.

September 27. At 8 a.m. we went for a walk with a group of men and six women, who took us to a place where they dug up roots, which they roasted and gave to us to taste - they were quite pleasant . The men retrieved more honey from the stingless bees, and they told us more about their diet - of how the women gather roots and berries and other wild foods and that this is supplemented by honey and occasionally meat. Many of the children go to a primary school, which offers free boarding; in fact uniforms and books and everything is free. A few go on to secondary school. Secondary school graduates generally do not return to teach in their own areas, this being part of the government policy of discouraging “tribalism” , but P knew a few Maasai teachers who were teaching in Maasai schools. Maloba, probably the oldest man, remembered the colonial period. We were left alone, we had more land, there were more animals, our life was easier. Now the government is always asking us for money for development; we sell honey to get the cash. In my colonial days, government policy was to leave indigenous people, like the Hadza and the Maasai, pretty much to their own devices. As long as they did not commit crimes against natural justice, (which were not clearly defined), we left them alone. After Independence, President Nyerere criticized this policy, saying that we had treated these peoples like a human zoo. He initiated a policy of development - schools, clinics, roads - and later, under the disastrous Ujamaa policy, insisted that these indigenous groups, who tended to live in small, dispersed groups, move into large settlements. The Hadza live in a semi-arid, harsh environment which, 50 years ago, had few attractions for anybody else. But with the growth in population and the increased pressure on all natural resources, including land, their lands have been nibbled away; some district game officers are thought to have sold, illegally, hunting rights to Arabs. It is increasingly difficult these days for the Hadza to find animals to hunt. In addition, the land has been encroached by neighbouring groups, including the Iraqw and the Tatoga, both of whom keep livestock – further increasing the pressure on land. Dorobo Safaris is the main player in helping the Hadza to retain control over at least some of their lands ,and to help them to live as some of them wish to live.

Later that day they showed us how they made arrows from the 5-inch nails which P had brought. One man is accepted as a specialist. Then they did some target shooting to test the arrows. That day they had seen a bushpig , which they tracked using their dogs and killed ; we watched them cut up and divide the meat among all the people.

After supper, four men and two women sat around the fire and sang haunting songs, full of both melancholy and joy.

|

|

arrow head |

target practice |

| |

|

|

|

| Ng'anyo & Dik Dik |

Making fire |

September 27. When we packed up camp, the Hadza women gladly drained what little water was left into their own containers: we had brought four 60L drums of water. Both Denise and I agreed that these five days, camping at Noa forest and then near the Hadza, were the highlight of our Safari, providing new experiences and fascinating glimpses into the lives of other people. We counted ourselves fortunate in being so easily accepted and welcomed by our Hadza hosts. It helped that we were only two: in a large group it would have been much more difficult to have the many personal encounters which we were privileged to have. And a major factor was the diplomacy and sensitivity of P, who was clearly regarded with affection and respect by the Hadza.

P and Kisana packing up

P and Kisana packing up

P and Kisana always packed with extreme care, which indeed was necessary, because space was limited at the back of our Land Rover. On our way we made a short detour to see Ng’onya’s house, or rather his grass hut, where we met his wife and little daughter.

P with Ng’onyo’s baby daughter

P with Ng’onyo’s baby daughter

Ng’onyo’s hut

Ng’onyo’s hut

Prickly pear on roadside

Prickly pear on roadside

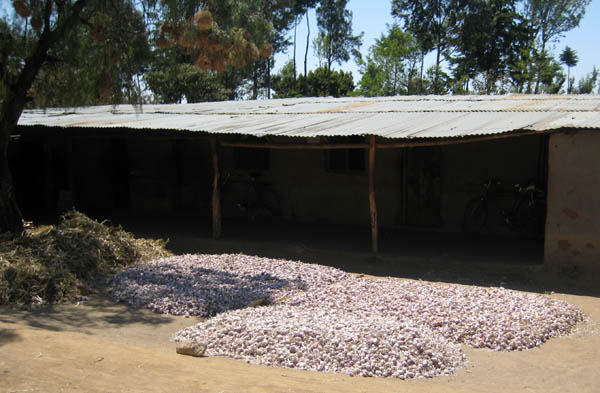

We passed great thickets of prickly pear, which distressed Denise because of its environmental damage. P pointed out that many of the small buildings were kilabu ya pombe (drinking bars). One fertile valley was planted almost exclusively with garlic, intended both for local consumption (mainly Zanzibar) and also for export to the Arabian Gulf. We saw a huge go-down (warehouse, or shed) for the garlic and also big heaps of garlic. Although it is obviously a useful cash crop for the local farmers, I wondered about its “water footprint”. ( I had recently read about the problems of asparagus fields in Peru, which use enormous quantities of water).

Garlic fields

Garlic fields

Garlic bulbs

Garlic bulbs

3 wheeled taxis at Karatu

3 wheeled taxis at Karatu

We arrived shortly after 3 p.m. at our next destination, the Octagon Safari Lodge in Karatu, which proved to be an oasis, with lovely gardens and large if somewhat impracticable cool rooms, and the luxury of a hot shower. This lodge is owned by an Irishman , as indicated by the posters of Guinness and Dublin in the bar; he is married to a Tanzanian lady, but both were away, leaving the young manager/receptionist/maître d' to do all the work.

Octagon Safari Lodge

Octagon Safari Lodge

At the bar we met two other guests, a couple, both 30 years old. Sean was from Venice, California and Daliana, his wife, from Ecuador. After dinner, we sipped Jameson's Irish whisky at the bar, more story-telling, and enjoying their company. They had ambitious plans for starting an eco-lodge in Ecuador and later settling in the Galapagos: Denise felt that they were hopelessly naïve and idealistic, but I enjoyed their youthful energy, charm and enthusiasm.

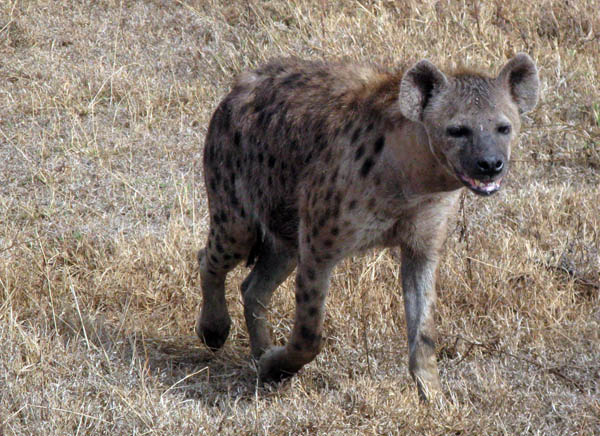

September 28. During these last four days, we stayed at Lodges, (Octagon, near Ngorongoro) and Tarangire Safari Lodge for Manyara and Tarangire National Parks. We spent the days touring the game parks, observing a wide variety of animals, and doing some rewarding birding – helped by Kisana’s sharp eyesight, with him spotting birds brilliantly. I am sure that you are familiar with African game parks, either from visits or from watching those outstanding TV programmes, so I shan’t give you details of all are encounters, just the highlights.

Zebra and flamingo at Ngorongoro Crater

I had been to Ngorongoro crater three times, first with Bernard in 1974, when we stayed at the splendid, and then affordable Crater Lodge – today it costs (high season) $1500 per person , sharing, per night. I went with my colleague Per Nilsson in 1981, and in 2007, with two young Swedes.The spectacular crater covers 250 sq. kms, and the surrounding Conservation area (where 40,000 Maasai live) extends over 8,350 sq.kms. The Maasai are not allowed to enter the crater, which caused them much distress. Now it is such a popular tourist attraction, that it would not be feasible to allow Maasai, and their cattle, into the crater. I had not much enjoyed my last visit to Ngorongoro -- not because of the young Swedish couple, who were delightful company –because there were so many tourist Combis, driven by aggressive drivers. Whenever lions were spotted, for example, Combis converged from all points of the compass. However, Denise wished to visit Ngorongoro, so we went and eventually I was glad: we had a good day, thanks in part to P’s skilful choice of where we went. Also, this time the Combi drivers were more considerate. The highlights of that day included seeing a nonchalant baby jackal sitting casually by the roadside quite unconcerned by my taking his photograph. We also had good views of hyenas as well as most of the other animals that are resident in the crater.

Baby Jackal

Baby Jackal

Hyena

Hyena

dik-dik

dik-dik

September 29 & 30. Denise and I stayed in luxury tents at Tarangire Safari Lodge, with rewarding game (and bird) drives each morning and in the late afternoon. During the five days when we were camping we had become close to P and Kisana, and we had lived in all African company. The Lodge was materially very comfortable, but it was disquieting for Denise and me: the guests, all foreign tourists, were all white, while the drivers and guides were all African. Having glimpsed where the drivers slept, I asked P if his accommodation was alright. P shook his head and said no it is not alright. P and Kisana - and all the drivers - were not allowed to join us at meals. This is probably the norm for this sort of superior establishment. There was nothing that Denise and I could do , but we both felt uneasy, being back in a racially segregated situation. P continued to be as agreeable and jocular as ever and he was pleased to introduce me to Elise, a pretty waitress who came from Kibondo -- where I had been stationed in 1952. She was surprised and delighted when I talked to her about Mwame Teresa, the Paramount Chieftainess of the BuHa.; Teresa and I were both new at our jobs and a little nervous, but we got on very well; Elsie was too young to have known Teresa, but she knew all about this impressive hereditary ruler.

Elephants viewed from Tarangire Lodge

Elise

Elise

After swimming my 10 lengths in the pool, I chatted to the attendant, who, on learning that I had been in the colonial service, asked me if I knew John Leslie, whose book on the history of Dar es Salaam he much admired. John, one of the best of all the DC’s , had been my District Commissioner at Kasulu in 1951: these sorts of conversations triggered memories of people and events that I had not thought of for many years. Why this man, who had been to college, was working as a pool attendant, I never discovered.

After dinner Denise and I met Annette, who, with her husband, owned the lodge; she had been born in Madagascar, of Scandinavian parents. Annette seemed very relaxed, so we tackled her about the accommodation for the drivers, and we were relieved to find that Annette admitted that it was unsatisfactory, and told us tht new accommodation was being built.

In the evening my body was covered with tse-tse fly bites, which were extremely irritating , making sleep difficult. In the morning P told me that I must be allergic to the tse-tse fly, which surprised me because both Kasulu and Kibondo districts were heavily infested with tse-tse fly, and I had suffered – admittedly that was long ago, in the early 1950s - many bites with no ill effects. And in the 1970s, Bernard and I were bitten numerous times whenever we drove to remote Kerie, in Mbeere.

Lion

Lion

Wildebeest at sunset

Wildebeest at sunset

October 1 Left at dawn, 6:15 a.m., for a last game drive when we had a great sighting of two lions and two lionesses, who allowed us to get good photographs. After breakfast we headed for Arusha, passing on the way a CCM (Chama cha Mapinduzi, “Party of the Revolution”, the governing party) convoy, which consisting of four luxury cars and a bus, all with loudspeakers blaring, for the forthcoming presidential elections. P was scathing about the CCM. I also saw an Islamic Secondary School, which is sponsored by Iran, and is free for Muslim scholars. P continued to be a fount of information, telling us that a game corridor was planned between Tarangire and Manyara National Parks, but this area had been invaded first by charcoal burners and then by Maasai and their cattle, and by others who had cut down all the large trees. We arrived at Dorobo Safaris in the early afternoon.

Elephant cow and calf

Elephant cow and calf

That evening Daudi and Trude took us the TST clubhouse for a TGIF party. (TST is a huge coffee estate and hunting area owned by a wealthy Texan; in terms of his lease, he was obliged to provide various amenities – including the club-house, and a school - for local residents. It was a very colonial situation, about 95% of the hundred or so people were white, including both old people and babies. However, the few African and Indians who were present were completely at ease. Having our drinks and snacks at a table on the lawn, I talked to George, an elderly Greek, who told me that in the 1950s there were 10,000 Greeks in Arusha; nearly all had left.

Daudi and Trude

Daudi and Trude

October 2. Denise left early this morning for her return flights to Cape Town. I give her A+ as a travelling companion, she was always good-humoured, flexible, considerate and curious. I liked the easy, entirely non-patronizing, manner of her conversations with P, and with Kisana.

I had another good bird walk with Daudi, thinking how fortunate I have been in birding in the company of several outstanding birders, the sort who can recognize a bird by its call, and who can spot birds, even in dense bush, in an instant. These experts include my colleague Ted Scudder (California) my two nephews Nevin Leesmay (Zambia and Zimbabwe) and Nigel Morris, (Florida and Brazil) and his son Rhett, and Ian Strange (Falklands) who lived in New Island, and who shared his ornithological knowledge with Bernard and me for a marvellous week in 1978.

Red and yellow barbet

Red and yellow barbet

That evening, my last evening in Tanzania. Daudi and Trude had invited two couples for another delicious vegetarian dinner. Steve was the brother of the owner of Tarangire Safari Lodge with his wife Marilyn, and their daughter Serena, who was on leave from working at a refugee camp in northern Kenya. Serena initially said little about her work, but when I questioned her, it was obvious that she worked under really arduous conditions. Serena's boyfriend , Andre, a South African, headed an anti-poaching unit for the TST estate. Coincidentally, he had spent four months in Kibondo, and he was one of the few people I've ever met who had seen the Malagarasi River, where I made my epic walking safari in 1952. Andre ‘s company is the biggest security company in East Africa, operating in seven countries with 16,000 guards; Andre complained that it was “top-light”. Between our hosts and the guests, we heard - and told - good stories, helped by a generous supply of South African wine (Porcupine Ridge).

Kisana Mollel

Kisana Mollel

October 3. Faithful Kisana called for me at 3:30 AM to drive me to Kilimanjaro Airport for my return flight via Nairobi and Johannesburg. My neighbour on the flight Johannesburg – Nairobi was a great contrast to the genial Mr. Motemba, on the outward flight. This man, who talked loudly and constantly to his friend in front of him, was a Somali whose elbow I constantly had to push gently back to his side of the seat. I arrived at Cape Town late afternoon to be met by Donald and driven home, after another memorable, trouble-free safari, where the highlights included our brief and unforgettable contact with the gentle, dignified Hadza, and meeting several outstanding people, including Denise, Pallangyo, Daudi and Trude.

We had also had good game viewing and birding: I saw 99 spp. birds, and the more active Denise racked up a total of 160 spp. These included bustard and bou-bou, camaroptera and cordon-bleu, purple grenadier and go-away bird, Ruppell’s robin chat and snake eagle tchagra and Abyssinian white-eye – just writing these magical names brings back my joy of seeing them in the bush. We saw 23 different mammals, including both silver-backed and golden jackals, bush hyrax, blue monkey and cheetah.

Iraqw girl and boy

___________________________________________________________________________________________

Appendix. The Hadza

(This is a summary of Daudi's two-page notes for tourists to the Yaida Valley)

The Yaida Valley Tourism Program began in the early 1990s when the Hadzabe community invited Dorobo Safaris, a small family-owned safari company, to bring tourists to the Yaida valley. The relationship between the Hadza ( as they are called in English) and the Peterson family goes back some 40 years, and it was of concern to both parties that tourism in the Valley serve the Hadza's needs and values. The invitation led to a carefully monitored program.

The Hadza, a small ethnic group of hunter gatherers, are the earliest known inhabitants of the Yaida Valley. Remarkably the Hadza have managed to keep their culture intact, despite many of the same pressures that have all but wiped out the world’s hunting and gathering societies since the advent of agriculture some 10,000 years ago . In the past few decades, however, the Hadza have lost as much as 90% of their former homeland to settlement by other ethnic groups .Today they number altogether between 1000 and 2000 people and the Yaida valley is one of their last stands.

The Yaida Valley Tourism Program is based on certain principles:

The Hadza have valuable knowledge that the rest of the world has lost. Hunting and gathering cultures, with their foundation of ecological prudence, have lessons to teach all people. What the Hadza would like you, as a visitor, to take home is an appreciation of their culture not as an antiquated tradition disconnected from the modern world, but as a valid part of it. This approach to tourism bolsters self-identity among the people victimized by severe prejudice and discrimination.

Community values and goals are paramount. Because Hadza land is a communal resource and Hadza society is egalitarian, tourism is judged worthwhile only if it enhances community land and resource rights. In particular, tourism should not permit individuals to profit at the expense of the community. Tourist proceeds go primarily to community accounts.

Yaida Valley Tourism Today.

The Yaida valley comprises three official villages, only one of which is dominated by the Hadza. The second is d ominated by Datoga pastoralists who are also victims of civilization’s march, having lost former homelands and moved more recently into the valley. The third is a mix of Iraqw, Iramba, Isanzu and Barabaig (a Datoga group) , all of whom have moved in from neighbouring areas. After seeing the benefits that tourism generated for the Hadza, the other two villages asked to be included in the program.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

The guidelines give advice to tourists:

Tourist camps should be located at least 1 km from Hadza Bush camps.

Visits to Bush Camps should generally last about two hours, never more than half a day. As a visitor, you can make the most of your limited time in the Valley by reading background information, and by going with an attitude of “just being”, participating if and when it seems appropriate. Visitors are asked not to purchase artifacts or give gifts. Failure to observe this guideline will quickly result in every encounter turning into a marketplace.

Visitors are also asked to take photographs only when permission has been given.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

The Dorobo Fund

In addition to acting as booking and monitoring agents, at the request of the three village governments, the Petersons have set up the Dorobo Fund to help the Hadza safeguard their land and resources, run by a team of highly dedicated Tanzanians the Dean found addresses works through government structures to address issue of land rights, immigration, and sustainable use of resources.

Neither the tourist program nor the Dorobo Fund aims to keep the Hadza as they are. That is their decision, Rather, the goal of both initiatives is to enable the Hadza to determine their own future, by protecting their land and resources.

- These are admirable and practicable guidelines. When I consider other examples of “ethno-tourism”, or when I look at the sorry plight of the Bushmen in South Africa, Namibia and Botswana, I wish that these rules could be universally applied to indigenous peoples.