Guys Disappearance

After the news of Guy’s disappearance, Ouma wrote:

Darling Guy, how much he too was beloved by all his old friends and held in such high esteem by all. Today’s post alone brought us over 30 letters and three wires and already I have had 29 glorious bouquets of flowers including every English flower available, daffodils, violets, narcissi, hyacinths, Bluebell hyacinths, wallflowers and Oh, the gorgeous roses and more and more roses. We will take them to hospital [for the patients] most of them and this is the first post since the news was in our papers.

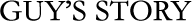

Decades later we were still dealing with Guy’s loss, each in our own way. In 1992, I met Jimmy Clark in Sherborne. He had been a pilot in Guy’s squadron on HMS Formidable, and through him I met Dick Phillips, whom I got to know fairly well and who provided me with one of the best accounts of Guy’s tragic disappearance.

Squadron 888 was based on the aircraft carrier HMS Formidable, which sailed from the Clyde in Scotland, on 17 February 1942. After calling at Freetown in Sierra Leone, Cape Town (but unfortunately not Durban) and

Bombay (Mumbai), the ship arrived at Colombo, Ceylon (Sri Lanka) on April 23 and started convoy duty between Colombo and Mombasa. Dick Phillips’ diary records the events of Guy’s mysterious disappearance from Formidable on 10/11 August 1942:

The Squadron flew ashore this morning to Port Reitz (near Mombasa) with every serviceable aeroplane – ten were ranged on deck in the early hours, but Brok1 couldn’t be found, so nine were catapulted and set off in three waves astern of the CO towards Mombasa. No one thought very much about Brok’s absence

The real seriousness of the situation only dawned on us when the ship came in and no signs of Brok had been revealed by the most intensive searches. His bed on the QD had been slept in, but there were no signs of his having dressed in the morning. Any suppositions as to how he disappeared so inexplicably must be unpleasant, but one can only assume that the darkness of that moonless night, he stumbled, perhaps sleep-walking, and fell over the side of the Quarter Deck.

The loss of Brok though, one can as yet scarcely realise it has happened, is the severest blow that the Squadron has suffered since its formation in November, for quite apart from his position as deputy Führer of the Squadron, and his irreplaceable qualities as a pilot, on whose prowess the reputation of the Squadron has been built up – he was perhaps the most universally popular man we have ever met. Brok as a pilot will never be forgotten, but he will be missed most as ‘one of the boys’.

Very special to my parents was this letter from Guy’s commanding admiral, Rear Admiral Arthur Bisset:

14th Aug.

Dear Judge Brokensha,

We are all terribly distressed about the loss of your son Guy. We do not know exactly how it occurred. He was last seen at about 11.45 p.m. on August 10 when he turned in, in his usual sleeping position, on a camp bed on the Quarter Deck. His squadron was due to fly ashore at 8.0 a.m. on the 11th and your son’s absence was not noticed until he failed to put in an appearance to fly his aircraft ashore. His bed had been slept in but he was not there at 6.0 a.m. when his servant went to the quarter deck to remove the bed. This was not unusual as he sometimes turned out early, and at the time his servant thought nothing of it.

We can only assume that at some time during the night your son turned out and in the dark managed to slip and somehow or other fell over the side; the ship was going fast at the time and being right aft any call for help would have had small chance of being heard.

I had had a long talk with your son about 5 p.m. on the 10th, discussing an exercise in which he had just taken part. He was in the very best spirits and was looking forward to going ashore next day when his squadron was to carry out some intensive training.

His loss is a very real one to the ship and his squadron as he was quite one of my best pilots.

I can assure you that there is no question that he was in any way unhappy or suffering from strain. He was always most cheerful and the best of mess mates.

I have written to his wife.

Please accept my own very real sympathy. These gallant flying lads do such magnificent work and we can ill afford to lose them.

Yours very sincerely,

Arthur Bisset, R. Admiral

Later Dad told me that there was a supposition that Guy had complained of stomach pains, perhaps colic, and the medical aide (there was no doctor on board) had advised him to wait

until Durban where he could be properly checked out. I am not sure whether this is true.

In his book I Sank the Bismarck, John Moffat describes meeting Guy:

One of them, whom I remember very well, was a South African, Guy (Brok) Brokensha, who had flown Skuas on Ark Royal. He had taken part in the attack on Mers-el-Kébir, and flown as part of a protective escort for the Swordfish who had torpedoed Strasbourg. He had become engaged in several dogfights with French fighters, during one of which he was turning to open fire when all his forward-firing machine guns jammed, as too did that of the observer in the rear cockpit. He manoeuvred his way out of it, though, and later helped shoot down a couple of attackers and was put forward for an award. In the same way that I had formed up with the ‘Black H Gang’ at St Vincent, I naturally seemed to get on well with anybody, like Brok, who was from the colonies. Brok was senior enough to be an instructor at Arbroath but this didn’t get in the way of our friendship.

The three of them [three of Moffat’s friends, including Guy] wanted me to give them a lift down to Edinburgh, dropping them off at Princes Street on my way home [on leave]. Brok was courting an attractive girl from Wick, whom he later married.

Later in the book Moffat gives an account of the fateful day of Guy’s disappearance.

… we left Colombo for Mombasa and then were due to sail on and call at Durban. One evening Brok Brokensha knocked on my cabin door and asked me to play a tune for him on my fiddle. Brok was an old colleague, originally a Skua pilot on Ark Royal; he was also one of my South African friends at Arbroath … We had met up again on the ‘Formy’ where he was flying Grumman Wildcats. He was a great pilot and had shot down several enemy aircraft, being awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.2 He had married a girl he met in Scotland, a real stunning beauty, and I liked him a great deal. He had the cabin opposite mine and we often spent time in each other’s company.

We sat and talked that night and I played, at his request, ‘Smoke gets in your eyes’ on my violin. Then we turned in, as I had to be on deck first thing, and I knew Brok was on the first combat air patrol to be launched at the next morning.

Next morning, Brok’s Martlet was ranged up and was scheduled to be the first for take-off, but there was no sign of him. Despite repeated calls on the tannoy for Lieutenant Brokensha to report to the flight deck, he still didn’t turn up, so eventually I climbed into the cockpit of his plane and taxied it out of the way, so that the rest of the section could take off. When the flying off was finished, I went down to Brok’s cabin. His bunk had not been slept in.3 We never found him. The carrier was searched from keel to flight deck, but there was not a trace of him. Brok came from Durban, and when we got there we had a difficult visit from his parents, who were naturally distraught, but couldn’t offer any reason for his disappearance. I was the last person to see him alive and continually went over in my mind that last evening that I saw him, when he had come to my cabin, but his behaviour had seemed perfectly normal. It was a complete mystery, and a very sad one.

Yes, it’s hard to realise that we have lost Brok and in such a tragic way. His time with us, though all too short, was well spent for he fired all with his enthusiasm for flying and for combat. Had we not had him with us as we grew up, we would still be very small beer indeed – but we will always remember him – as Scottie says – as a polished pilot and as a mate in a thousand.

HMS Formidable docked in Durban five days after the tragedy and Dad met the commander and some of Guy’s fellow pilots. Dad later told me that he had applied his legal mind to close questioning of the captain and others, and was satisfied that there had been no party that night: drinking was not allowed when they were on active service. There was no suggestion that Guy was in any way depressed – he knew that the ship would be calling at Durban in a few days’ time and that he would see his parents for the first time in five years. He also knew that when he returned to Britain he would be based in Wick, with his own Squadron, and would be able to be with Margaret and Deirdre. Guy had everything to look forward to.

- Pronounced ‘Brock’.

- This is a mistake; it was in fact the Distinguished Service Cross.

- His camp bed on the quarterdeck had, however, been slept in – as mentioned in the other quotations above.